4 Deseeding Energy Consumption of Network Stacks

The cross-factor is a per-frame energy toll that can be ascribed to the fact that every frame received or transmitted through a wireles interface requires some processing in the device’s network stack. The aim of this chapter is to break down the cross-factor into its constituent parts in order to comprehend the underlying causes, all within the scope of providing an accurate mathematical description of the cross-factor which would give the energy model an unprecedented specificity. This may enable us to evaluate old energy efficiency strategies and to propose and test new schemes, both at a device and at a network level.

Our proposal, with respect to the work by Serrano et al. (2015), is to switch to a more generic target platform, which will provide us an easy access to powerful kernel instrumentation, as described in the previous chapter, present in most general-purpose Linux-based distributions.

To be able to conduct fine-grained energy debugging of the network stack, we must somehow isolate the network activity from the consumption of the rest of the system. To this aim, the next section is devoted to dissect and discuss the components of a laptop computer in order to understand their implications in the global power consumption, and how to minimise their impact. Then, subsequent sections explore the roots of the cross-factor.

4.1 Anatomy of a Laptop Computer

A laptop computer is a complex and power-hungry piece of hardware. It comprises a number of components, both hardware (battery, screen, hard disk drive, fan, wireless card, RAM memory, CPU) and software (services, kernel, drivers), that require a thorough discussion. Some of them are not present in other devices (e.g., the fan), and some others are essentially different in terms of performance and power requirements.

Battery

The battery is a serious obstacle for energy measurements. Although using it as power source is actually possible, it is totally impractical because it prevents long term experiments, and the constant need for recharging is a waste of time. Then, the use of an external power source is highly advisable, but in this case the battery must be removed to avoid noise coming from battery charging and discharging.

Nevertheless, usually supplying DC power through the power jack socket is not enough. Most manufacturers are interested in forcing the user to acquire and use original parts. As a consequence, most laptops are capable of detecting the AC adapter and take unexpected21 decisions. This is generally done through a third connection in the power jack. For example, in the case of Dell computers, this third wire goes to a transistor-shaped component placed in the AC transformer. Actually, this component is a small memory that can be read using a 1-wire protocol. It stores a serial number that identifies the AC adapter.

Summing up, if the laptop does not detect this memory, the BIOS can do improper22 things. For instance, we detected that Dell computers’ BIOS do not allow the OS to control CPU frequency scaling. Fortunately, it is very straightforward to borrow such a component from an official AC adapter and attach it permanently to the third connection of the power jack socket. In this way, any power source looks as an original part to the BIOS, and the OS kernel can freely manage all the system’s capabilities.

Screen

Same as for smartphones (Carroll and Heiser 2010), the screen is the most energy-hungry component in a laptop computer. It typically accounts for more than a half of the total energy consumed when the computer is just powered on and idling. Thus, the screen constitutes a very high and variable (as it depends on the GPU activity) baseline consumption that must be avoided in wireless experiments. In Linux, this can be done by finding the backlight device entry in the /sys/class subsystem and simply resetting it, so that the screen is permanently powered off.

Hard Disk Drive

Regarding the system’s non-volatile memory, we cannot get rid of it because it is needed for the OS storage. Commonly, laptops are equipped with hard disk drives (HDD), which are mechanical devices powered with voltages ranging from 5 to 12 V. HDDs are proven to be energy-hungry devices (Hylick et al. 2008) with a consumption variability in ascending order of tens of Watts. As a consequence, every read/write during an experiment generates an intractable noise.

On the other hand, all the devices studied in Serrano et al. (2015) use flash memories. This kind of non-volatile memory is the best option, because its consumption variability is three orders of magnitude below HDD’s (Grupp et al. 2009). In our experiments, we replaced the original HDD by a solid-state disk (SSD). Given that an SSD is composed of NAND flash units, its consumption is much smaller and far more stable.

Fan

The thermal characteristics of a laptop computer require a cooling subsystem: heat sinks (CPU and GPU), air ducts and typically one fan (at least). The fan is regulated dynamically with a pulse-width modulation (PWM) technique. This component becomes an unpredictable source of electrical noise, as its operation point depends on the computer’s thermal state.

Suppressing the fan is not an option because, at some point, the CPU will heat and the computer will turn off. Our solution was to set it at fixed medium speed with the help of the i8k kernel module and the i8kfan user-space application.

Wireless Card

This is the last part of the wireless transmission chain and the first of the reception one. In principle, the energy models in the literature assure us that a linear behaviour is expected, independently of the manufacturer or model. However, there are a couple of factors that may lead us to select a particular card.

- Supported capabilities

- Nowadays, it is very difficult to perform interference-free wireless experiments over ISM bands without an anechoic chamber23. The 2.4 GHz band is typically overcrowded, while in the 5 GHz band we have better chances to find a clear channel. Thus, an 802.11a-capable card is advisable.

- Manufacturer

- Distinct manufacturers (and models) have better or worse driver support in the Linux kernel. For instance, Intel PRO/Wireless cards are known for requiring a binary firmware to operate. On the other hand, Atheros released some source from their binary HAL to help the open-source community add support for their chips. As a result, there are completely free and open-source FullMAC24 drivers available for all Atheros chipsets.

All our experiments were conducted using the Atheros AR9280-based 802.11a/b/g/n Half Mini-PCI Express card that was characterised in Section 3.4.1.

RAM Memory

The random-access memory is a fundamental peripheral device in a computer system: it holds the instructions of the running programs —the OS kernel included— and the data associated. Therefore, our first guess was that the RAM memory could play a meaningful role in the energy consumption of a wireless communication.

CPU

The CPU is another power-hungry component. For many years, the first CPUs were like bulbs: they were consuming the same power whether they were doing something useful or not. In fact, they executed junk code (i.e., a loop of NOPs) during idle time. Later, CPU architects realised that more intelligent things can be done in such periods of time (for instance, enabling some kind of energy-saving mechanism).

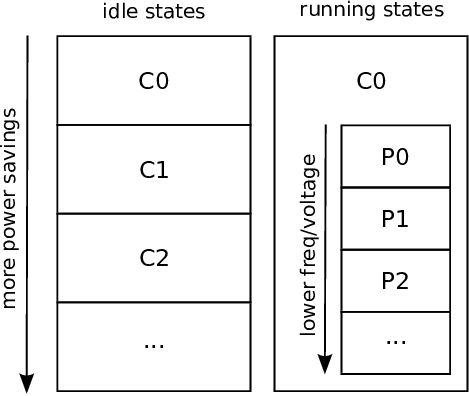

Figure 4.1: CPU P- and C-states.

Nowadays, CPUs are becoming more and more complex. Without seeking to be exhaustive, a modern CPU has arithmetic control units (ALUs), pipelines, a control unit, registers, several levels of cache, some clocks, etcetera. But more interestingly, modern CPUs implement several power management mechanisms (see Figure 4.1), which are covered by the Advanced Configuration and Power Interface (ACPI).

- P-states

- Also known as frequency scaling. When the CPU is running (i.e., executing instructions), one of these states apply. P0 means maximum power and frequency. As Px increases, the voltage is lower and, thus, the frequency of the clock, and thus the energy consumed, is scaled down.

- C-states

- When the CPU is idle, it enters a Cx state. C0 means maximum power, because junk code is being executed. This can be a little bit confusing because, as Figure 4.1 shows, the CPU is also in C0 when it is running. In general, C0 means the CPU is busy doing something, whether executing actual programs (running) or something not useful (idle). In C1, the CPU is halted, and can return to an executing state almost instantaneously. In C2, the main clock is stopped and, as Cx increases, more and more functional units are shut off. As a consequence, returning from a deep C-state is very expensive in terms of latency.

For example, Intel Haswell processors support up to eight C-states: C1, C1E, C3, C6, C7s, C8, C9, C10. However, the BIOS just reports two C-states to the ACPI driver, which are called C1 and C2. We have verified, by comparing idle consumptions for each C-state, that the correspondence is as follows:

- ACPI C1 corresponds to Intel C1: the CPU is halted and stops executing instructions when it enters into idle mode.

- ACPI C2 corresponds to Intel C6: this is a new sleep state introduced in the Haswell architecture.

Finally, multicore systems introduce additional complexity, because the OS decides how many cores become active at any time, and each core has its own power management subsystem (i.e., P- and C-states). Therefore, our experiments are always carried out in single-core mode to simplify the analysis.

Services

There may be a lot of active user-space services (also called daemons) in a Linux system by default. They can add noise to our measurements in two ways: by consuming CPU time and writing logs to disk. Hence, identifying and disabling not essential services is desirable.

Kernel

There exist two power management subsystems for each CPU in the Linux kernel: cpufreq25 controls P-states and cpuidle26 controls C-states. Both subsystems have a similar architecture, separating mechanism (driver27) from policy (governor28).

- The

cpufreqgovernor - has several policies that focus on certain P-states or frequencies to the detriment of others, e.g.,

performance(high frequencies) orpowersave(low frequencies). It is also possible to manually fix certain frequency or range of frequencies. - The

cpuidlegovernor - takes in the next timer event as main input. Each C-state has a certain energy cost and exit latency. Thus, intuitively there are two decision factors that the governor must consider: the energy break-even point and the performance impact. The next timer event is a good predictor in many cases, but not perfect since there are other sources of wake-ups (e.g., interrupts). Therefore, it computes a correction factor using an array of 12 independent factors through a running average. Moreover, it is possible to manually disable the C-states (excepting C0).

Drivers

All Linux drivers are compiled as separate modules. In particular, wireless drivers29, along with the entire 802.11 subsystem, can be compiled out-of-tree within the backports project30. This is very useful in order to use the latest drivers on older kernels.

The wireless driver module interacts directly with the network interface controller (NIC). In our case, the selected card uses the ath9k driver. The function ath9k_tx() is the entry point for the transmission path. The driver fills the transmission descriptors, copies the buffer into the NIC memory and sets up several registers that trigger the transmission.

In order to conduct energy breakdowns like the one depicted in Figure 3.5, Serrano et al. (2015) claim that their methodology discards packets right after the driver. This statement becomes uncertain when a closer look at any wireless driver is taken. According to our experiments, discarding a frame before the buffer is copied into the NIC implies that only half of the driver is actually taken into account for the cross-factor value. On the other hand, if we try to discard it in the very last instruction of the driver (i.e., avoiding setting the register that triggers the hardware transmission), then the module crashes if the NIC’s memory is not cleaned up, a non-trivial task that anyway would consume more energy. Due to this, and combined to the fact that drivers differ greatly from one to another, we do not include the driver into the definition of cross-factor, given the difficulty of isolating driver and NIC consumptions.

As with the variety of drivers mentioned above, a similar argument can be wield against the user-space consumption. Therefore and from here on, we define kernel cross-factor as the energy consumed from the system call that delivers the message until the driver is reached. Cross-factor, as is, maintains the original definition given by Serrano et al. (2015) to avoid confusion.

We would also like to highlight that our way of interrupting the transmission path by discarding a frame in the driver is a bit different from Serrano et al. (2015). They conducted this breakdown by commenting a driver function. This method implies the need for recompiling the driver, which is time-consuming and not very portable31.

For our part, we generate packets with a short string at the beginning of packet payloads. The presence of this magic string triggers the packet drop. Our method, despite introducing a very small overhead, is agile and portable (for instance, it can be implemented on the fly using SystemTap).

The laptop computer selected for our experiments is a Dell Latitude E5540 with Intel Core i5-4300U CPU at 1.9 GHz and 8 GB of SODIMM DDR3 RAM at 1.6 GHz, equipped with an Atheros AR9280-based 802.11a/b/g/n Half Mini-PCI Express card. In our measurements, we use Fedora-default pre-compiled kernels. We arranged two separate partitions: one with Fedora 12 and kernel version 2.6.32 and the other with Fedora 20 and kernel 3.14. Only the latter supports Intel-specific drivers, thus we use ACPI drivers only in order to operate under similar conditions.

4.2 Cross-Factor: Separating the Wheat from the Chaff

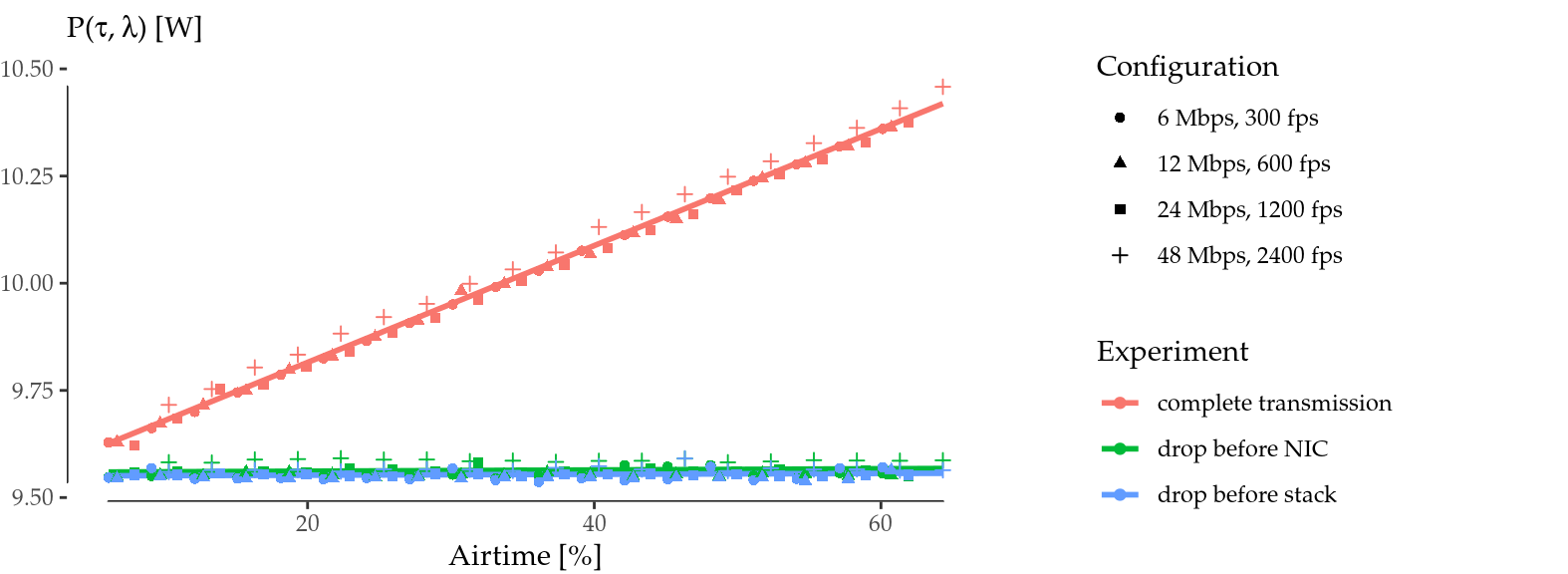

We have identified the two main components suspected of being responsible of the cross-factor: CPU and RAM memory. Our first priority is to isolate and quantify the impact of the RAM. It is not possible to regulate its activity, but this can be done for the CPU. For this purpose, the CPU was fixed at P0-C0 states, i.e., always running at maximum frequency, maximum energy consumption. We performed an energy breakdown using this configuration in kernel 3.14 and the results are shown in Figure 4.2.

Figure 4.2: Energy breakdown with the CPU fixed at P0-C0 states.

The lines appear superimposed: the laptop is consuming the same power among different parameters, different packet rates. Hence, one important conclusion to be drawn is that the RAM memory has no significant impact in the overall energy consumption of wireless transmissions. The noise can be ascribed to the fact that not all the instructions consume exactly the same energy (Tiwari et al. 1996). Other possible sources of noise are cache and pipeline flushes.

With this simple experiment, we have demonstrated that the CPU is the leading cause of cross-factor in laptops, and it is clear that the cpuidle subsystem has a central role, because a CPU spends most of the time in idle mode (Barroso and Hölzle 2007). From now on, and in order to take a deeper look at C-states, we remove a variable by keeping the P-state fixed at P0 (maximum frequency).

4.3 Power Consumption in Unattended Idle Mode

The Soekris net4826-48 used in Section 3.3.1 is equipped with an AMD Geode SC1100 CPU that supports ACPI C1, C2 and C3 states32. Unfortunately, it seems that Linux distributions for embed devices, such as Voyage Linux, disable cpuidle in their kernels, which means that the OS has no control over the idle mode. In such conditions, we know now that the CPU cannot be in C0 all the time, because the device does not consume the same power with different parameters. What is happening then?

Back to our laptop, it is possible to disable cpuidle through the kernel command-line. The idle power consumption in this situation, which we call unattended idle mode, reveals that the laptop is entering C1. This fact can be extrapolated to the Soekris case, which makes sense, since there is no governor to resolve which C-state is the more suitable at any given time. Thus, the processor simply halts when there is no work to do.

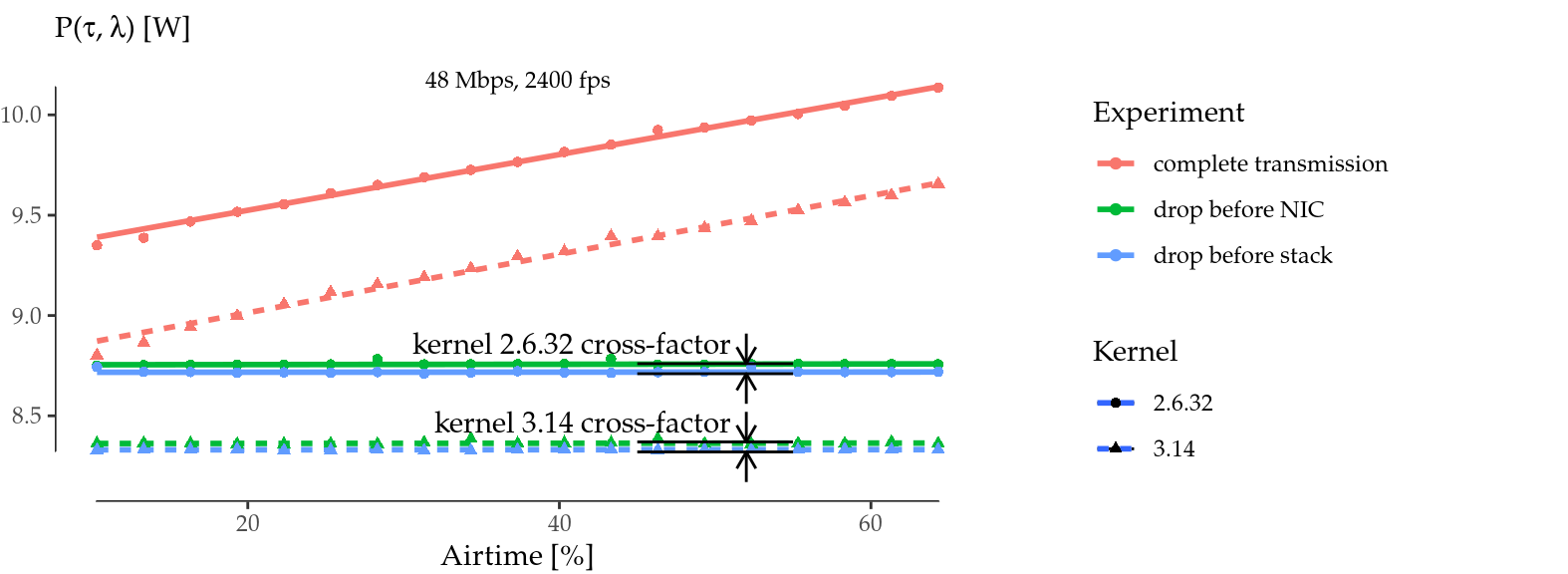

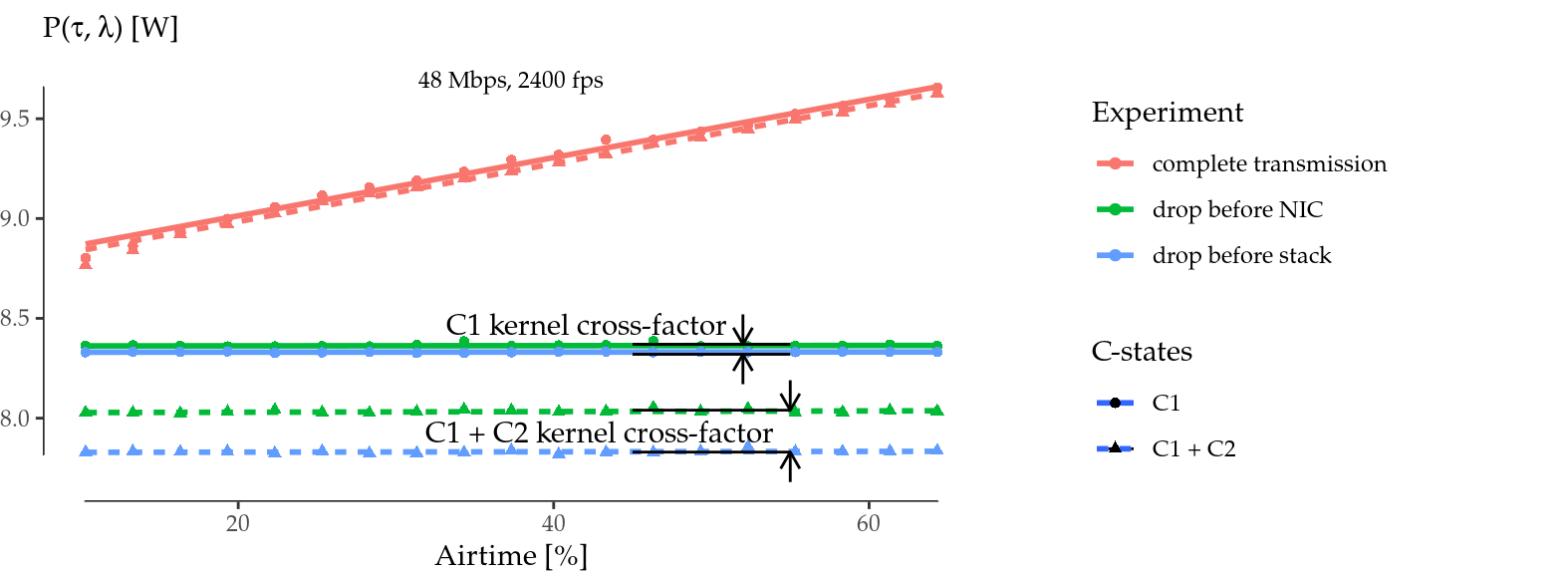

Figure 4.3: Power consumption breakdown vs. airtime with fixed C1 state for kernels 2.6.32 and 3.14.

Figure 4.3 shows the energy breakdown for both kernels, 2.6.32 and 3.14, when only the C1 state is enabled. As can be seen, the obtained kernel cross-factor is almost negligible, which suggests that Intel Haswell’s C1 state saves a very small amount of power, unlike the Soekris’ C1 state as shown in Figure 3.5.

There is also a baseline power difference between kernels. This offset can be ascribed to several factors. For instance, a lot of code has changed —and probably improved— between those kernel versions. In particular, the scheduler and the cpuidle algorithms have evolved. Moreover, the compiler used has changed also.

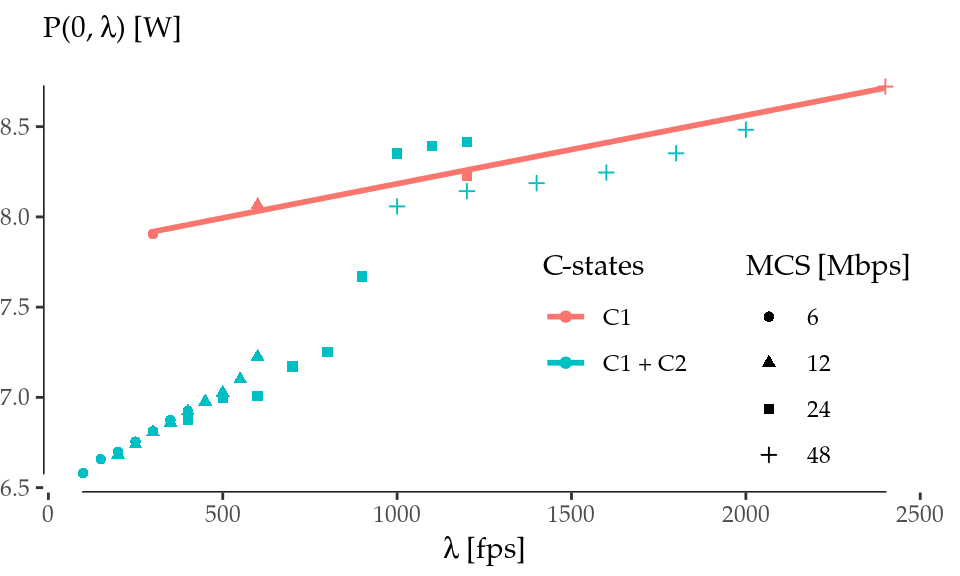

At this respect, we can calculate the complete cross-factor (including the user-space, as done in Section 3.3.1) by extracting the slopes of the regressions of Figure 4.4. These values are comparable to the Linksys case reported by Serrano et al. (2015): \(0.51(2)\) mJ (kernel 2.6.32) and \(0.38(2)\) mJ (kernel 3.14).

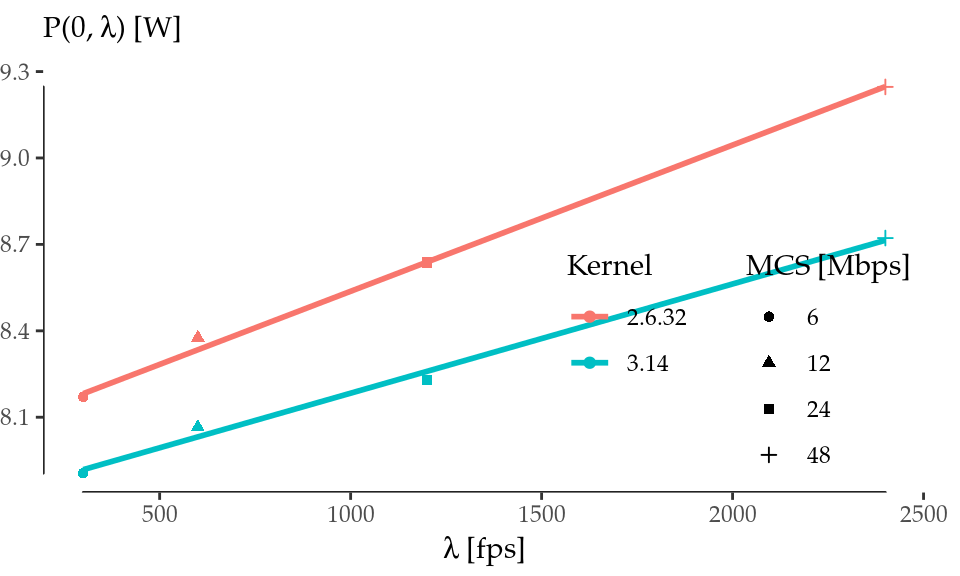

Figure 4.4: Power consumption offset (\(\tau=0\)) vs. framerate with fixed C1 state for kernels 2.6.32 and 3.14.

It is also important to note that, unlike the results from Figure 3.5, there is absolutely no dependence on the frame size in this case. Our guess is that RAM memory consumption would be proportional to the frame size and may have a small but still perceptible impact in low-power devices, but it is negligible compared to the consumption of a laptop’s CPU. As a consequence, the frame size can be removed as a parameter from the cross-factor analysis in laptops.

4.4 Power Consumption with Full cpuidle Subsystem

With the knowledge acquired so far, we can move onto a more realistic scenario by enabling the whole cpuidle subsystem, i.e., keeping both ACPI C-states enabled and letting the governor decide.

Figure 4.5: Power consumption breakdown vs. airtime with two cpuidle configurations for kernel 3.14.

Figure 4.5 depicts the energy breakdown for kernel 3.14 with full cpuidle subsystem (C1+C2 enabled) and compares it to the previous case (C1 only). By enabling C2, the consumption appears to be always lower up to driver level (blue and green lines). Nevertheless, the consumption of complete transmissions (red lines) is lower in the 300 fps case (not shown here), but it is the same in the 2400 fps case.

Figure 4.6: Power consumption offset (\(\tau=0\)) vs. framerate with two cpuidle configurations for kernel 3.14.

Figure 4.6 compares the offsets of complete transmissions in Figure 4.5 for both cases: C1+C2 and C1 only. The red line corresponds to C1: as expected, its behaviour is linear as seen in Figure 4.4. On the other hand, the C1+C2 case (blue points) is not linear globally. It comprises three clearly distinct parts: when the framerate is low, there is an approximately linear behaviour because the CPU only uses C2; when the framerate is high, C2 is no longer used, and the slope matches the red line; between them, the behaviour becomes unpredictable because of the mix of C1 and C2. Therefore, the cross-factor as defined by Serrano et al. (2015) makes no sense anymore. When all the C-states are active, there is no linear behaviour anymore: we cannot talk neither about a slope nor a fixed energy toll per frame.

Furthermore, we had assumed, as Serrano et al. (2015), that we can simply drop the packets at certain points, measure the mean power up to those points and represent all this as an energy breakdown. But obviously this is not true either. For instance, Figure 4.5 shows that the CPU is not entering C2 when complete transmissions are performed, and the consumption is the same as in the C1-only case. On the other hand, the CPU is clearly spending some time in C2 when the frames are dropped earlier. Even it seems that the network stack is consuming more power because the energy gap (between green and blue lines) is larger. Evidently, it should be the opposite: the stack would be consuming less power as soon as it enters a lower C-state.

4.5 Exploring the cpuidle Subsystem

As stated in previous sections, the cpuidle subsystem is a very complex component. Kernel timer events are the main input for the governor algorithm as they often indicate the next wake-up of the CPU, but the running average used to scale the latter makes it unpredictable, since it depends on the recent state of the whole machine. The purpose of this section is to shed some light on the linkage between the residence time of C-states, the number of wake-ups per second, the CPU load and the transmission of wireless frames.

We implemented a very simple application33 with two modes of operation: it is capable of setting a kernel timer at a given constant rate and, when this timer is triggered, it (i) does nothing or (ii) sends a UDP packet. At the same time, it calculates the mean residence time of each C-state over the whole execution.

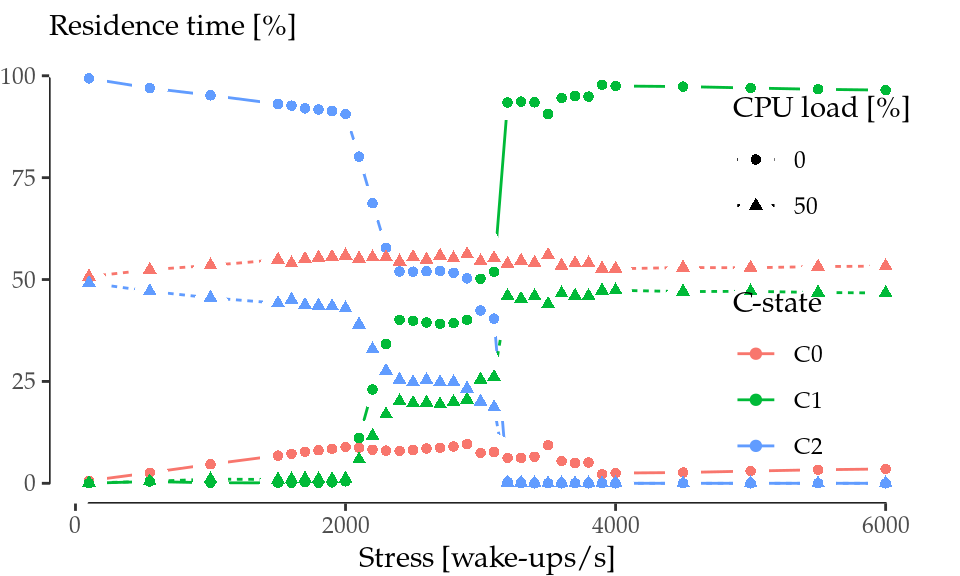

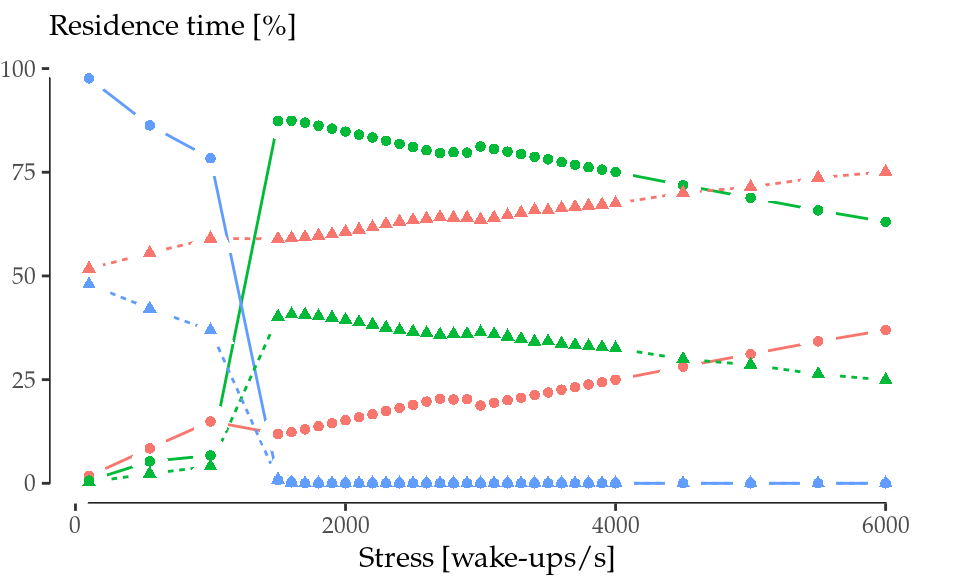

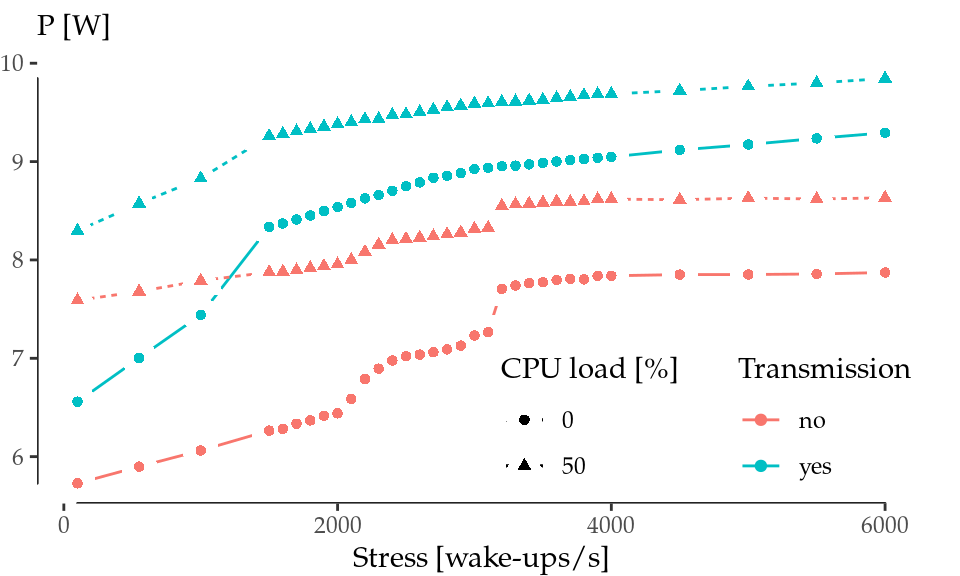

Figures 4.7 have been compiled using this tool. The additional CPU load was added on top of the latter using a modified version of lookbusy34. Figure 4.8 compares the two previous figures in terms of power consumption.

Figure 4.7: Residence time of each C-state vs. wake-ups/s for kernel 3.14. Each wake-up does nothing (left) or performs a UDP transmission (right).

Figure 4.8: Power consumption offset vs. wake-ups/s for kernel 3.14.

In Figure 4.7 (left), the only source of wake-ups is the kernel timer that our tool sets. Each C-state is represented by a different colour, and shapes and line types distinguish between CPU loads. The first observation is that the addition of a substantial source of CPU load has no impact on the distribution of residence times. Another important observation is that, up to 2000 and from 3500 wake-ups/s onwards, there is only one active idle state (C2 or C1 respectively), and the behaviour is linear. This fact can be verified by checking the power consumption (Figure 4.8, red lines). From 2000 to 3500 wake-ups/s, the transition between C-states occurs in a non-linear way.

In Figure 4.7 (right), on other hand, there is another source of wake-ups: hardware interrupts caused by the wireless card each time a packet is sent. The transition between states occurs earlier because there is actually twice the number of wake-ups. And, again, the CPU load shows no impact on the distribution of residence times.

These are partial results and are limited to constant rate wake-ups, but these findings are in line with the non-linearities previously discovered in the cross-factor and they confirms the enormous complexity we face.

4.6 Summary

This chapter follows the path set out by Serrano et al. (2015) with the discovery of the cross-factor, an energy toll not accounted by classical energy models and associated to the very fact that frames are processed along the network stack. We have introduced the laptop as a more suitable device to perform whole-device energy measurements in order to deseed the root causes of the cross-factor by taking advantage of the wide range of debugging tools that such platform enables.

Our results (Ucar, Azcorra, and Banchs 2014; Ucar and Azcorra 2015), albeit preliminary, provide several fundamental insights on this matter:

- We have identified the CPU as the leading cause of the cross-factor in laptops. Thus, the cross-factor shows absolutely no dependence on the frame size, because the RAM memory has no significant impact in the overall energy consumption of wireless transmissions. On the other hand, low-powered devices, like the Soekris, show a very small but perceptible dependency that can be ascribed to the RAM memory.

- The CPU’s C-state management plays a central role in the energy consumption, because a CPU spends most of the time in idle mode.

- When the C-state management subsystem is not present in the OS, the device enters C1 in idle mode (halted) and cannot benefit from lower idle states.

- In contrast to low-powered devices, the C1 state of a laptop’s CPU saves a very small amount of power.

- With a fully functional C-state management subsystem, the linear behaviour disappears. In consequence, we cannot talk about cross-factor as a fixed energy toll per frame.

- A non-linear behaviour implies that we cannot perform energy breakdowns by dropping packets inside the transmission chain. Therefore, new methodologies and techniques are required to enable energy debugging.

- C-state residence times depend primarily on the number of wake-ups per second produced by software and hardware interrupts. However, they show no dependence on the CPU load.

Further research is needed in order to fully understand the key role of the C-state subsystem in the energy consumption of wireless communications, as well as to investigate other processor capabilities not accounted for in this work, such as P-states and multicore support.

References

Barroso, Luiz André, and Urs Hölzle. 2007. “The Case for Energy-Proportional Computing.” Computer 40 (12): 33–37. https://doi.org/10.1109/MC.2007.443.

Carroll, Aaron, and Gernot Heiser. 2010. “An Analysis of Power Consumption in a Smartphone.” In USENIX Annual Technical Conference, 14:21–21. Boston, MA.

Grupp, L.M., AM. Caulfield, J. Coburn, S. Swanson, E. Yaakobi, P.H. Siegel, and J.K. Wolf. 2009. “Characterizing flash memory: Anomalies, observations, and applications.”

Hylick, Anthony, Ripduman Sohan, Andrew Rice, and Brian Jones. 2008. “An Analysis of Hard Drive Energy Consumption.” In 2008 Ieee International Symposium on Modeling, Analysis and Simulation of Computers and Telecommunication Systems, 1–10. IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/MASCOT.2008.4770567.

Serrano, P., A. Garcia-Saavedra, G. Bianchi, A. Banchs, and A. Azcorra. 2015. “Per-Frame Energy Consumption in 802.11 Devices and Its Implication on Modeling and Design.” IEEE/ACM Transactions on Networking 23 (4): 1243–56. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNET.2014.2322262.

Tiwari, Vivek, Sharad Malik, Andrew Wolfe, and Mike Tien-Chien Lee. 1996. “Instruction level power analysis and optimization of software.” Journal of VLSI Signal Processing Systems for Signal, Image, and Video Technology 13 (2-3). Kluwer Academic Publishers: 223–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01130407.

Ucar, Iñaki, and Arturo Azcorra. 2015. “Deseeding energy consumption of network stacks.” In IEEE 1st International Forum on Research and Technologies for Society and Industry Leveraging a Better Tomorrow (Rtsi), 7–16. https://doi.org/10.1109/RTSI.2015.7325085.

Ucar, Iñaki, Arturo Azcorra, and Albert Banchs. 2014. “Deseeding Energy Consumption of Network Stacks.” In 6th Annual International Imdea Networks Workshop.

That is, unexpected… for the user.↩

Again, improper… from the user’s standpoint.↩

Especially when all your fellows work in similar research topics.↩

See https://wireless.wiki.kernel.org/en/developers/documentation/glossary for the definition of FullMAC and SoftMAC drivers.↩

It provides the platform-dependent state detection capability and the mechanisms to support entry/exit into/from different states. By default, there exists an ACPI driver that implements standard APIs. Usually, CPU-specific drivers are capable of detecting more states than ACPI-compliant ones.↩

It is an algorithm that takes in several system parameters as input and decides the state to activate.↩

Think, for instance, about a similar task for a function contained in the kernel core.↩

Available at https://github.com/Enchufa2/udperf↩